The Inactivity Paradox

Some inactive people don't get pain or sickness. The reason why can improve your health, fitness, and performance.

Summary of today’s post

Inactivity is a source of pain and disease in Western people.

Some people are just as inactive as people in the West, yet they avoid pain and disease.

If you can change how you rest, you can improve your health and performance and avoid pain.

We’ll explain the “inactivity mismatch hypothesis” and four practical ways to improve how you rest to get all the benefits.

Housekeeping

Full access to today’s post, like all Wednesday and Friday 2% posts, is for Members.

Become a Member below—we save you more time and money than our monthly cost.

We have a winner for the Clearspace 2% Screen Time Challenge. User name: Sjvantilburg. Congrats. Shoot me an email. Thanks to all who participated—I received a lot of great messages from people whose screen time plummeted.

Podcast preview—the full Member podcast is at this post’s bottom

2% With Michael Easter: The Inactivity Paradox on Apple Podcasts

Now onto the post …

Last week, we covered a fascinating new study that uncovered the top two forms of exercise for preventing and treating back pain. Read it here if you missed it.

A key reason why we get back pain, many researchers think, is how much time we spend inactive.

They argue our sedentary time is also perhaps the largest factor in the main factor in our primary killers like heart disease, certain cancers, diabetes, and more.

But there’s a problem with that argument: There are populations who spend just as much time inactive as we do. Yet …

They don’t seem to get back, hip, and knee pain.

They have much lower rates of our primary killers.

Today, we’re exploring that disconnect. We’ll dive into some curious findings about inactivity and health.

Call it “the inactivity paradox.” It suggests that inactivity is only part of our problem.

The lessons from this paradox can reduce your risk of pain, help you perform better, and decrease your risk of dying early from disease. The result: You’ll live better and longer.

The inactivity paradox

Section summary

Being inactive hurts us, yet we evolved to be inactive. Some hunter-gatherer tribes are rather inactive but don’t get diseases.

The details

David Raichlen, an anthropologist at the University of Southern California, noticed a strange paradox. He wrote:

Recent work suggests human physiology is not well adapted to prolonged periods of inactivity, with time spent sitting increasing cardiovascular disease and mortality risk … These inactivity-associated health risks are somewhat paradoxical, since evolutionary pressures tend to favor energy-minimizing strategies, including rest.

In other words, being inactive hurts us. Yet we evolved to be inactive.

For example, a recent study noted that being sedentary increases your risk of, well … pretty much everything: Death, heart disease, cancer risk, diabetes, osteoporosis, depression, cognitive impairment, etc, etc, etc.

To understand more about this strange inactivity paradox, Raichlen traveled to Tanzania to study the Hadza.

The Hadza are a tribe of hunter-gatherers who live similarly to our early ancestors. Scientists study hunter-gatherers to understand how humans lived for most of our history, which can give insights into how we adapted to live.

But this wasn’t a standard study with the obvious “inactivity is bad” outcome.

In his past trips to Tanzania, Raichlen had noticed something strange: The Hadza seemed to spend just as much time being inactive as we do.

They seemed to lounge around for a lot of the day. And yet they don’t get the chronic diseases and pains we do.

The hunter-gatherer inactivity study

In short

The scientists strapped activity trackers and muscle activation trackers to the Hadza. They found they spend just as much time being inactive as us—but their inactivity is much different than ours.

The details

Raichlen wanted to confirm whether his observation was true. So brought an arsenal of gear to the Tanzanian bush:

Scientific-grade activity trackers to measure the tribe’s time spent walking versus resting.

Portable EMG machines to measure the muscle activity of the tribes as they rested.

Notebooks and cameras to document the details of how they rested.

Tribe members wore the activity trackers all day. As tribe members rested in camp, Raichlen documented how they rested and used his EMG machine to measure their muscle activity.

His surprising finding:

The Hadza spent 9.8 hours a day at rest.

That figure is more than we rest.

People in the U.S. spend about 9 daily hours at rest. Other developed countries rest about about the same amount.

His notes and the EMG data revealed the difference.

The Hadza rest differently than us.

We rest comfortably—the Hadza don’t

Section summary

The Hadza rest in ways that require a low level of muscle activity, which helps keep them healthy. We rest in chairs, which require no activity.

The details

When we rest, we sit in comfortable chairs or couches.

But Raichlen discovered that when the tribe rested, they sat on the ground. Or lied, kneeled, or even held a bodyweight squat position.

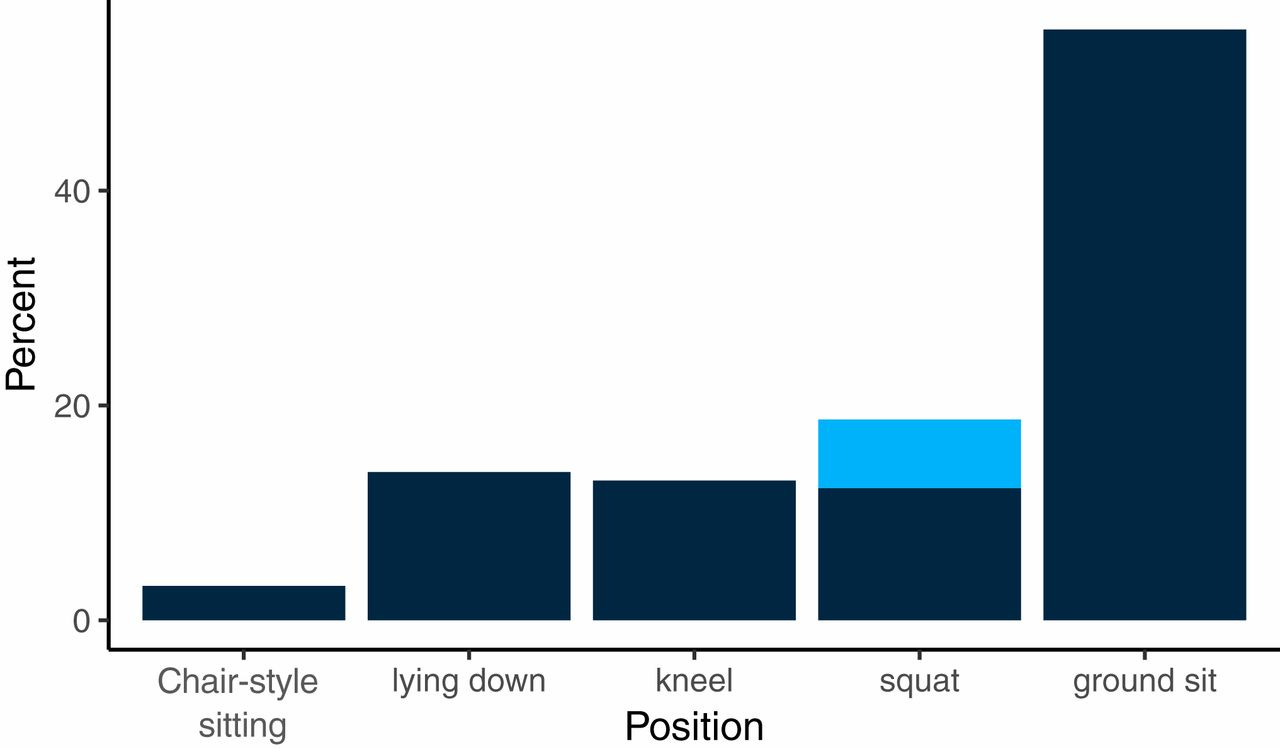

Here’s how much time tribe members spent in different rest positions.

Kneeling, squatting, and ground sitting isn’t free. It lightly engages all the muscles in your lower body and trunk.

Consider squatting—you have to activate your lower body and trunk to keep yourself up. When sitting on the ground, you must activate your legs and core to keep your torso propped.

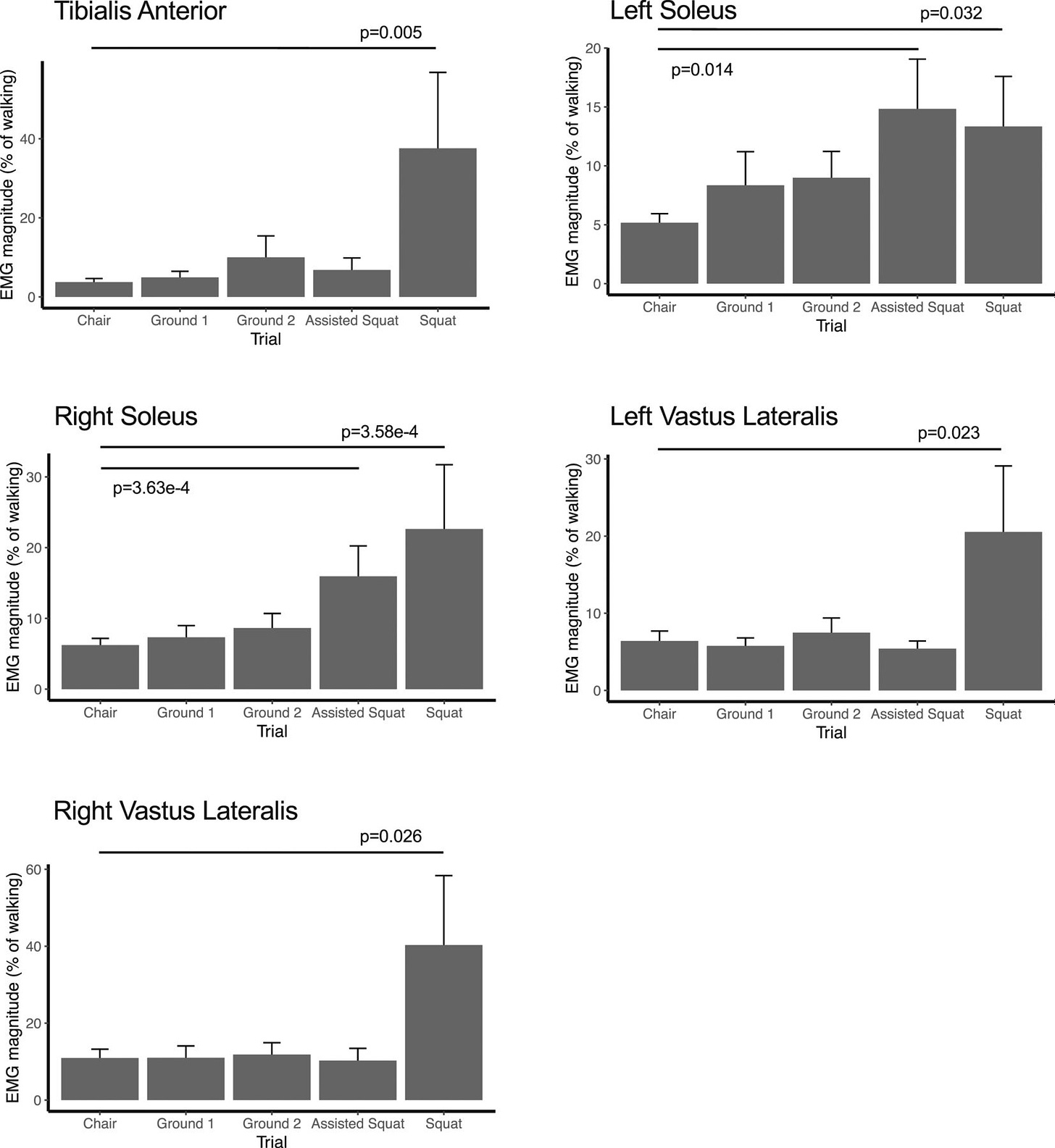

This showed in the data. Here are the EMG muscle activation readings for different muscle groups in each position.

Our comfortable chairs do that muscular work for us. When we sit in comfy chairs, we don’t so much sit as we do melt into their cushioning. Each of our muscles slackens like we’ve gone brain-dead.

The entire reason chairs are comfortable is because they require less physical effort—they do the work our muscles would normally do in rest positions.

And we sit comfortably all the time—at the office in a chair with seven different dials for optimal comfort. Or in a padded dining chair when we eat. Or in a overstuffed sofa to watch Netflix or read. All comfortable chairs—all the time.

Meanwhile, the Hadza don’t use chairs. They spend nearly two daily hours in the bodyweight squat position, which, as you can see above, requires muscle activation to sustain.

The inactivity mismatch hypothesis

Section summary

We evolved to be mildly active at rest. Chairs removed this light activity—weakening our bodies and hurting our health.

The details

Raichlen calls his theory the “inactivity mismatch hypothesis.” He wrote:

This hypothesis posits that our physiology evolved within the context of a high duration of sustained muscle activity throughout all parts of the waking day, both through physical activity and through resting postures that maintain low levels of muscle activity. Prolonged periods of muscular inactivity during chair sitting, a common element of daily life in industrialized populations, are best viewed as a key mismatch with our evolutionary past.

In other words, we evolved to be mildly active even at rest.

But our modern rest postures—sitting in chairs—have removed that.

It’s just one other significant way we’ve removed effort from our days—and paid the price.

For example, research shows that our type of inactivity—with no muscle activation—is associated with the accumulation of higher levels of circulating triglycerides and cholesterol, increasing our risk of heart disease.

Yet the Hadza don’t get heart disease—they’re more active, their diet is different, and even their rest is active. It’s tougher for the bad stuff to accumulate when you’re always working.

Another problem with chairs

Section summary

Chairs also elevate our risk of back pain.

The details

How we sit also seems to factor into our high rates of back pain.

Back pain is rare among the Hadza. About the Hadza, Raichlen told me, “Squatting or sitting without their backs resting (on a chair back), unsurprisingly, increased their lower back muscle activation significantly.”

But our modern chairs remove the light work our muscles used to do as we rested. Muscle is use-it-or-lose-it stuff. Just 10 days of not using a muscle significantly shrinks it.

So our backs become weaker over time. Then, when we chair-weakened people bend over to lift something or move into a new position, our bodies are more brittle.

Pain sets in. Recall from last Wednesday that 85 percent of back pain is labeled “non-specific,” which is unseeable pain that appears from the ether. Scientists at Harvard estimate that the way we now live causes 97 percent of this non-specific back pain.

Four ways to rest better

Section summary

Do these four things to rest better and improve how you feel and perform so you can live long and well.

The details

Thinkers like Katy Bowman, Kelly and Juliet Starrett, Ido Portal, and others argue that we need to rethink how we rest.

Here are a four ways to revamp your rest.