Post summary

This post is the most comprehensive guide to rucking.

It answers the most common questions about rucking.

Housekeeping

Want full access to health, fitness, nutrition, and mindset information that you’ll actually use? Become a Member of Two Percent. We only publish what really matters.

Join the Don’t Die retreat. We’ve got just a few spots left.

Audio/podcast version of this post

The post

My book, The Comfort Crisis, generated considerable interest in rucking. The New York Times said the book helped kicked off the rucking craze.

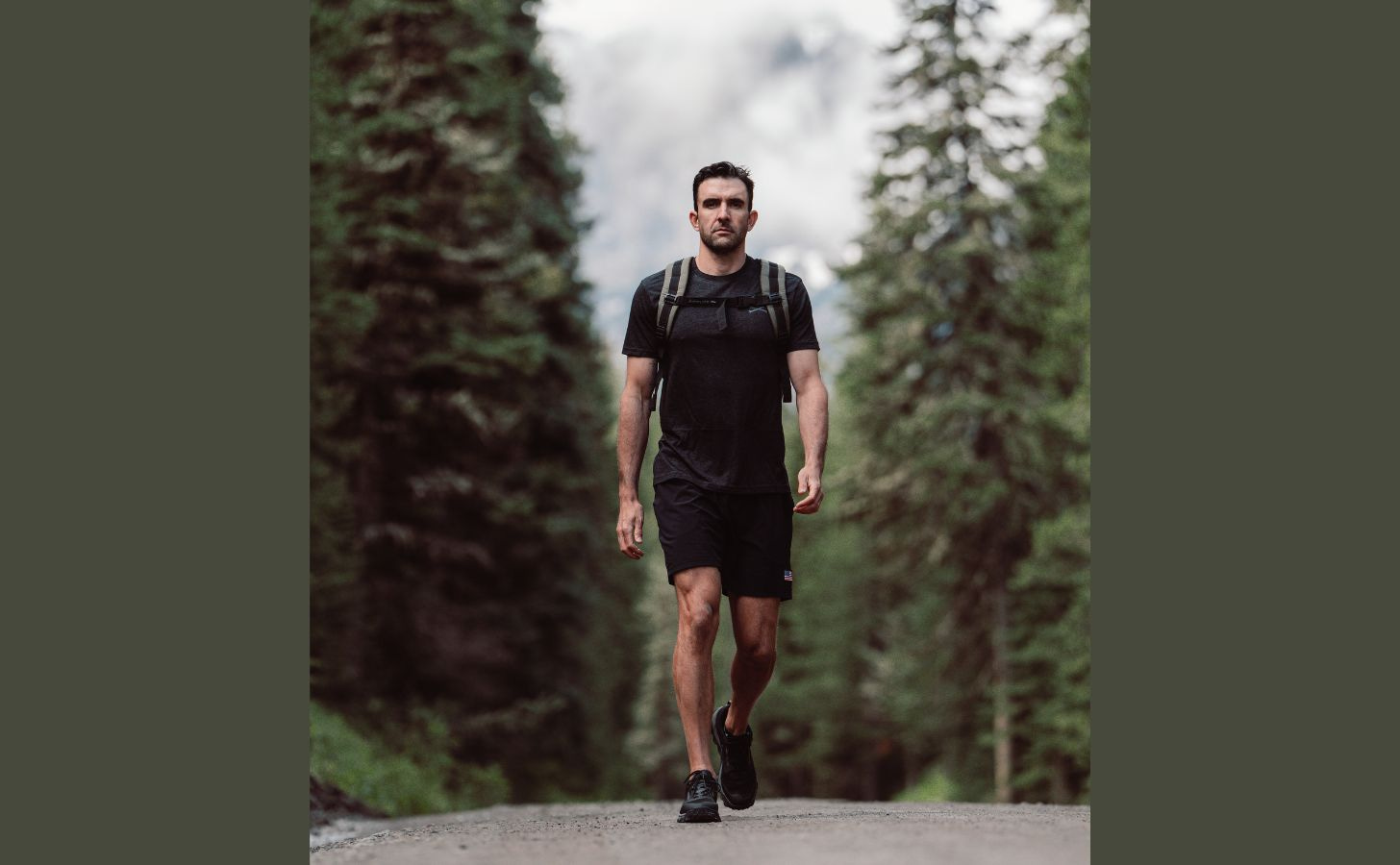

“Rucking” is just walking with weight in a backpack. And walking with weight is the great missing link in human health and fitness.

Humans are, in fact, “born to carry.” We evolved to walk great distances while carrying weight. But our need to carry was largely rendered moot to technology. We have shopping carts, wheeled suitcases, strollers, vehicles, moving Dollies, semi-trucks, forklifts, etc.

Carrying is powerful. It’s a sort of mix between strength and cardio that works wonders for your health, fitness, and mindset.

To understand why humans should walk while carrying weight, read The Comfort Crisis (buy a signed copy here). The book unpacks the full historical argument—it’s led people ranging from ages 8 to 88 who hate exercise to take up rucking.

But since the book’s publication, I’ve received a lot of follow-up questions.

This post answers many of those question. Welcome to rucking 101.

Let’s roll …

How many calories does rucking burn?

Short answer: This depends on the equation and pack weight, but rucking on average burns an average of 20 to 300 percent more calories than walking.

Long answer: The number of calories you burn while rucking rises or falls based on various factors like the weight in the ruck, the terrain, etc. But it also depends on how you calculate calorie burn (there are various equations).

Calorie burn, however, is just a way to measure work. And if a person is measuring work in calories (and not time or distance, which are performance metrics), it suggests to me that the person wants to change how their body looks.

Looking “better” (as we define it in modern society) requires two things: Fat loss and muscle growth or preservation.

Rucking is better for fat loss compared to lifting because it burns anywhere from 20 to 133 percent more calories than lifting.

Rucking is better for fat loss compared to running because it actively works your muscles with weight. This stimulates muscle growth or, at least, tells your body to not get rid of muscle.

In other words, rucking helps you avoid the sometimes doughy, excess bulk from lifting as well as that skinny-fat look that running can sometimes produce.

Consider a study on backcountry hunters. A backcountry hunt requires rucking outdoors with anywhere 25 to 80 pounds on your back the entire time.

Over 12 days, a group of backcountry hunters/ruckers lost a lot of fat, preserved muscle, and saw fitness and health markers rise. Here are the numbers:

Body Fat: Down 14%

Muscle Mass: Up 0.1% (you’d expect a loss in muscle mass, but rucking prevented that).

VO2 Max: Up 8.4%

LDL Cholesterol: Down 28.7%

That said, I think it’s more important in the long term to think about the health implications of rucking and body type. So …

Rucking and the SUPERMEDIUM build

Short answer: Rucking creates a body type that is harder to kill. This applies to both men and women but for different reasons. We call it being SUPERMEDIUM.

Long answer: We call the type of build that rucking gives you “SUPERMEDIUM.” It’s not too thin, but it’s also not too muscular.

Rucking corrects for body type:

Have too much fat or muscle? Rucking will lean you out.

Too skinny? You’ll get stronger and put on a healthy amount of muscle.

Women often need a little more muscle than they have (which we’ll cover more in depth below).

But men often have the opposite problem. Men often try to build extra muscle just for the sake of it—they often think that more muscle = healthier. But that isn't always the case.

I started thinking about this more after spending a week with my good friend Trevor Kashey.

Saying Trevor is smart is like saying Lebron James is good at basketball. The kid’s a genius—he graduated college at 18, got a Ph.D. in biochemistry at 23, did cancer research, and now owns Trevor Kashey Nutrition, where he’s helped people (many of them dire cases) lose a collective 200,000+ pounds and win Olympic gold medals.

Trevor appears in The Comfort Crisis. His wisdom in the book may change how you think about nutrition forever.

I spoke with Trevor about muscle, and he was explaining to me why more isn’t always better. He told me to think about intraspecies variation:

If you compare two healthy, full-grown animals of the same species, the smaller one will probably have a longer life span. Think of a Great Dane versus a Chihuahua—the Chihuahua lives more than twice as long on average. And there are a number of reasons for that. Like oxidative damage, inflammation, organ stress, joint stress, etc. This is why BMI is so important.

Lots of fit but very muscle-bound men will be like, ‘BMI is irrelevant, because it puts me in the overweight category, and look at me, I’m not overweight, I’m just super jacked!’ But I take the position that huge amounts of muscle mass causes different and probably worse strain on your organs compared to an equal amount of fat. The difference between being overweight with lean mass versus overweight with fat mass is what organs get stressed out and fail first.

Huge amounts of muscle mass means ton of vascular strain, which means more stress on your heart. Huge amounts of fat means tons of visceral fat which leads to liver, and pancreatic issues. So let’s say you have a bodybuilder and a couch potato who are both in the ‘obese’ category according to BMI. Both are going to die younger than necessary, but the bodybuilder will have a heart attack and the couch potato will get diabetic nephropathy … and probably a heart attack.

Be harder to kill. Be SUPERMEDIUM.

Should women ruck?

Short answer: Yes, yes, and yes.

Long answer: I didn’t expect this question, but here we are. Here are three stellar reasons why women should ruck (I could have listed more):

1. It’s weight training for people who don’t like the weight room

The U.S. government commissions teams of our top scientists to analyze hundreds of studies on exercise to determine an ideal dose for health.

Their conclusions: everyone should do at least 150 weekly minutes of endurance activity and strength train twice a week.

Yet only 19 percent of women hit the exercise recommendations, while 26 percent of men do.

Why the difference? Women and men do endurance exercise at about the same rate, but women are far less likely to strength train.

There are many reasons for this. For example, cultural stigma and weight rooms filled with creepy, sweaty, grunting dudes.

Rucking combines endurance and strength. It allows women to meet those guidelines and get stronger without setting foot in a weight room.

This is critical because scientists are just now realizing that not having enough muscle can be far more dangerous for women than an unhealthy scale weight.

A recent study of 50,000 Canadian women, for example, found those most at risk of death registered a “healthy” BMI but had the lowest levels of lean muscle. (I can do a deep dive on women and muscle if that’s of interest. Just let me know in the comments).

2. Rucking strengthens bones

Everyone starts losing bone density around age 30.

But women after menopause begin losing it at a rapid and dangerous rate. This is why bone fractures are one of the biggest health threats to women.

Aging women in the U.S. are two, five, and eight times more likely to break a bone than they are to have a heart attack, get breast cancer, or have a stroke, respectively.

If you break an arm, it’s an annoyance that’ll heal. But if you break a hip, you’re essentially screwed. About 50 percent of people over age 65 who break their hip are dead within six months.

The best way to stop and even reverse bone loss is to do “aerobic walking where you’re bearing weight,” according to Dr. Robert Wermers, a bone disease specialist with the Mayo Clinic. I.e., rucking.

One study found that aging women who trained with a weight vest didn’t lose bone, while those who trained without a weight vest saw a loss in bone density. The scientists say the earlier in life you start rucking the better you’ll be.

3. Women are damn good at carrying

I believe that what humans were built to do can inform a lot of what we should do today—and humans were built to carry.

Historical data suggests that women did significantly more carrying than men.

There’s a lot of old anthropological research backing this idea. One of my favorite studies focuses on the women of the Seri hunter-gatherer tribe on Tiburon Island in the Gulf of California.

In 1895, WJ McGee, who ran the Bureau of American Ethnology, traveled to the island to study the tribe. He observed that the women frequently made a 15-mile round trip excursion from the beach up into the mountains—through a gnarly landscape of mesquite, cactus, and agave.

They’d fetch water and “rapid walk” it back to camp in heavy, awkward clay jugs. He stated that the women of the tribe were “notable burden bearers.”

I told you all that because paleo fitness and diet books tend to picture “man” or “men” as the super-fit hunter. And they use that imagery to persuade modern men to exercise.

But the reality is that hunter-gatherer women seemed to have worked physically harder and longer than the men (and you still see this phenomenon in exercise studies today … women consistently go harder in interval workouts).

So next time you’re rucking and you think it sucks, just remember the women of the Seri tribe, the “notable burden bearers,” and remind yourself that you got this.

What about injuries?

Short Answer: Rucking seems to be much safer than running and mildly safer than lifting.

Long Answer: Let’s focus on two studies to understand injuries in rucking versus other activities.

Study one

Researchers at the University of Pittsburgh tracked 451 soldiers in the 101st Airborne. Over a year, the group had 133 injuries. Twenty-eight of those injuries came from exercise.

The findings: soldiers were 6 times more likely to get injured running and about 2.3 times more likely to get injured lifting.

Here’s how the data broke down:

Rucking: 3 injuries

Lifting: 7 injuries

Running: 18 injuries

Study two

Researchers followed 800 soldiers going through Special Forces Assessment and Selection. It’s the 20-ish day hell soldiers go through to see if they can become Special Forces operators.

So you had 800 men rucking nonstop with ~50 pounds for days on end. And this was all at the highest intensities across the gnarliest of terrains.

When the scientists looked at the data, they discovered that rucking caused 36 injuries. The most common injuries were sprains, tendonitis, or non-specific pain.

For context: We had 800 soldiers wearing relatively heavy rucks and going absolutely bonkers through untamed landscape for days on end. And just 4.5 percent of them got injured.

This is why I feel rather confident telling you that the average ruck is incredibly safe. Compared to those soldiers, you’re doing the same activity with less weight, at a less insane pace, for a few hours a week in your neighborhood or on a trail.

Of note: The researchers tracked the injury rates of other activities the soldiers did during Assessment and Selection, like running and obstacle courses. They found rucking had the lowest injury rate. Running and the obstacle course resulted in two and four times as many injuries, respectively.

Of course, the risk of injury while rucking depends on how heavy your ruck is. Which leads me to …

How much weight should I ruck with?

Short answer: For everyday rucking for health and fitness, men should stick to between 20 and 45 pounds, while women might want to hang out in the 15-to-35-pound zone. But new ruckers should ease in.

Long answer: I’m going to pull directly from The Comfort Crisis:

Prehistoric cave art depicts warriors heading into tribal battles with crude shields and spears. Together these items could weigh between 10 and 20 pounds. Thousands of years ago Greek Hoplites, Roman Legions, and Byzantine infantrymen all marched with 30 pounds of gear. Fighters in all regiments around the world until the mid-1800s carried between 20 and 35 pounds.

Then British Soldiers in the Crimean War began carrying 65 pounds. Loads crept successively higher in World Wars One and Two, and in Korea and Vietnam. By the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the average soldier was marching with about 100 pounds.

In the aftermath of the Crimean War, British scientists investigated the impacts of a soldier’s load on his ability to fight war. Any infantryman, they found, could move quickly and safely marching with 50 pounds. About 150 years later, in the 2000s, three different studies from US Army, Marines, and Navy all confirmed the finding. Fifty pounds is the heaviest load that allows soldiers to fight like hell, become physically bulletproof, and forge elite strength and endurance.

In other words, stay under 50 pounds. That’s a quick and easy guideline.

But it’s obviously not super nuanced. For example, rucking with 50 pounds is experienced differently by someone who weighs 110 pounds versus someone who weighs 220 pounds.

In 1950, Colonel S.L.A. Marshall did a lot of research and concluded that 1/3 of bodyweight is the heaviest you should ever go. That guideline is particularly helpful if you weigh less than 150 pounds and are searching for a safe but heavy weight.

But what if I’m overweight?

At the same time, people were generally fitter and weighed less in the 1950s. So I think using 1/3 of your bodyweight if your BMI is above 25 may be too much. (Calculate your BMI here).

Here’s a guide to the heaviest amount of weight you should ruck with if your BMI is over 25.

Big takeaway from this section

Because most people are rucking for general health and fitness, I think using 15 to 50 pounds is ideal.

The calorie burn data suggests there isn’t as much of a calorie burn benefit going over 50lbs as you would think. (A nerdy way to put that: The relationship between pack weight and calorie burn isn’t necessarily linear … there’s a point of diminishing returns.)

I’m just starting to ruck. What weight should I start with?

Short answer: 10 to 25ish pounds.

Long answer: In 2010, a team of military researchers wondered how they could optimize ruck training for military recruits.

They wanted to come up with some general pointers the military could use to get new, doughy kids into fighting shape but also not push them so hard they got injured or totally burned out.

After spending a bunch of time, effort, and money reading all the research, the scientists developed a set of guidelines that were … basically common sense.

They discovered that rucking newbies should:

Ruck at least once a week (this allowed their body to adapt and improve).

Not ruck so often that you don’t have time to recover (don’t do three tough days in a row).

Not use too heavy of a weight too soon.

Progress by increasing either the load or distance, but not both at once.

Do other stuff that makes them fit. E.g., Strength training and mobility work.

Rucking is inherently uncomfortable. It wouldn’t work if it were easy.

But you want to start with a weight that allows you to hit the sweet spot where you’re uncomfortable but walking normally. I.e., The weight shouldn’t be so heavy that you’re severely hunched over.

For the average active person, 10 to 25ish pounds is a good starting point.

But gauge how you feel. If you weigh 100 pounds and 10 pounds feels too heavy, go lighter. If you’re a CrossFit maniac and 25 pounds feels way too light, go heavier.

Should I ever go above 50 pounds or 1/3 bodyweight? And how should I do that?

Short answer: Rucking with heavier loads can be useful for certain people. For example, military members and backcountry hunters. But in training, I generally only ruck with more than 50 pounds on a treadmill or Stairmaster.

Long answer: In Alaska, I rucked with 80 pounds on my back most days for a month straight. That was well over 1/3 bodyweight for me.

During a pack out, I had to ruck more than five miles and all uphill with over 100 pounds on my back.

So in training for the expedition, I had a bit of a catch-22:

Training with super heavy loads can be a bit risky. If I hurt myself, I may have had to cancel the trip.

Yet if I didn’t train with super heavy loads, I wouldn’t be ready.

The heavy rucking solution

I consulted some research and smart people and came up with a plan:

When I trained with over 50 pounds, I’d do it on a treadmill or Stairmaster.

I’d fill my ruck with anywhere from 60 to 90 pounds.

Then I’d set a treadmill to its highest incline (15%) and walk anywhere from 2 to 4 miles an hour for 30 to 90 minutes.

This allowed me to get in heavy, uphill training in a safer manner.

I generally view indoor training (i.e., gyms) as sterile, boring, controlled environments that allow me to “get ready” to do cool stuff outside.

A lot of the risk from rucking with over 50 pounds comes from the inherently unpredictable nature of the outdoors.

I’m willing to accept risk on the big outdoor mission—for example, my trip to Alaska—but not in training for it.

An inclined treadmill or stair machine gave me a totally predictable, forgiving surface. I didn’t have to worry about gnarly terrain that could lead me to roll an ankle or blow out a knee (80 pounds on your back can tip any stumble into a fracture.)

That said, I don’t think heavy gym rucking is necessary unless you have something coming up where you’ll be forced to ruck with 70 or more pounds.

My shoulders ache when I ruck. What should I do?

Short answer: Ruck more, wear your ruck around the house to strengthen your shoulders, use a hip belt, and do this mobility exercise.

Long answer: I ran this past my great friend Dr. Doug Kechijian, DPT (he’s worth consulting if you live in the NY, CT, NJ area).

Doug is a former Special Forces soldier (which means he’s done a lot of rucking) who became a Doctor of Physical Therapy and now owns Resilient Performance Physical Therapy.

He put it to me this way: “Rucking isn’t comfortable. Shoulder discomfort while rucking is kind of normal. It obviously sucks more the heavier the weight is.”

That said, three methods can help.

1. Fidget with the straps and use the hip belt

Doug said, “To get over shoulder discomfort, I fidget with shoulder straps constantly. Or, if I have a hip belt, I’ll at times take almost all the tension off my shoulders and let almost all the weight ride on the hip belt.”

2. Wear your ruck at home

When people ruck, they usually go 30 to 120 minutes, which is a long time for your shoulders to be weighed down if they aren’t used to it.

So wear your ruck at home for short stints throughout the day. Start with 5 to 15 minute increments. Wear your ruck as you clean the house, wash dishes, stand at your desk, etc.

This will help your shoulders accumulate more time under the ruck, which can strengthen them without the aches. (P.S. I usually wear my ruck when I clean up around the house ... it sneaks in a workout!)

3. Do the exercise that fixes rucking shoulder pain

Should I use a hip belt?

Short answer: Hip belts are super helpful, especially when the weight feels heavy.

Long answer: When I was in Alaska, my 80-pound pack was essentially my conjoined fraternal twin.

Hip belts allow you to shift the load around to different muscle groups so no one group gets tired enough to slow you down.

In Alaska, I’d go for 15ish minutes with the weight riding mostly on the shoulder straps. Eventually, those shoulder straps would feel like they were trying to slice me lengthwise into thirds.

So I’d pull the hip belt tight and loosen the shoulder straps, allowing the weight to ride mostly on my hips.

After another 15 minutes, my lower body muscles would begin to feel like they were being burned off my body. So then I’d do something in between, where the weight was equally distributed between the belt and shoulder straps.

But I also use a hip belt at home on lighter rucks. Tip: Attach a dog leash to the hip belt so you can walk your dog hands free.

Where should my hip belt be positioned?

A couple of people have asked where they should position the hip belt. “On your hips” was my first thought. :)

Backpackers say your hip belt should be up high, resting at the top of your hip bones. This backpacking ideology, naturally, has trickled into the rucking circles.

But the thing about backpackers is that they tend to be dorks about having the lightest pack possible. Out on the Appalachian Trail, for example, backpackers shoot for a pack that is no heavier than 30 pounds. I’ve even heard of ultralight backpackers cutting half the handle off of their toothbrush just to save an ounce. Dorks! :)

Us ruckers embrace the weight. Our rucks are heavy for the sake of being heavy. This is why backpacking rules don’t always apply to rucking.

I emailed back and forth with Jason at GORUCK on this (he did a ton of very heavy rucking as a Green Beret). We both came to the same basic conclusion. Here’s what I wrote him:

“My experience in Alaska and doing some heavier rucks is this: I don't overthink the belt placement. I just cinch it where it feels most natural at any given time. Heavy rucking sucks. I use the belt and straps in whatever way makes it suck less. Frequent transitions in belt and load placement seem to help that. I don’t think there’s one ‘magic spot.’”

He agreed and added that placing the belt lower on the hips seems to be better for him and other SOF soldiers because it allows you to breath better.

Should I ruck with a weight vest or a ruck?

Short answer: Probably a ruck.

Long answer: Before I get all dorky, let me say this: that you carry weight for distance is far more important than how you carry weight for distance.

Now for the nuance. The best resource for this question is this Two Percent post: Rucking: Backpacks Vs. Weight Vests.

I’ll summarize the main points here. But for most people most of the time, a ruck is a better option.

Rucks are better for distances that feel “far” to you.

Rucks are more practical.

Rucks are safer when you’re fatigued.

Rucking may help back injuries.

Rucks allow you to breathe and dissipate heat better.

Vests are easier to load correctly.

Vests are ideal if you’re a military member or police officer.

So if you buy just one thing, make it a pack that you fill with weight. Or just buy both and be ready for any party that comes your way.

Should I run with my ruck on?

Short answer: Probably not.

Long answer: Running was critical to human evolution (more on that in The Comfort Crisis).

Those humans were “essentially professional athletes whose livelihood required them to be physically active,” one Harvard anthropologist told me.

To stay alive, early humans had to be very physically versatile. They were good at just about every physical skill, from movement to endurance to strength.

On the other hand, modern people in the developed world sit an average of 6 to 8 hours a day (and that stat was taken before COVID quarantines).

Our inactive lifestyles give us weird muscle weaknesses, strength imbalances, and restricted movement patterns.

We’re also heavier people. For example, the average hunter-gatherer weighs around 125 pounds. The average American man and woman weigh 200 and 170 pounds, respectively.

So when we run, we do so with our wonky movement patterns, weaknesses, and heavy bodies. You can see how this might be problematic.

It’s probably why anywhere from “27% to 70% of recreational and competitive distance runners sustain an overuse running injury during any 1-year period,” according to one massive review of the research on running and injuries.

Adding weight to running increases a person’s injury risk further.

A group of scientists at the University of Wisconsin studied this exact topic and found that running with a 20-pound weight vest was a bad idea. It led to force changes that would likely bring about runner’s knee relatively quicker.

Obviously, plenty of people run a couple of miles with a 20-pound vest during the annual Murph workout, and their knees don’t spontaneously combust afterward.

So you’ll probably be fine if you do it now and then, but I wouldn’t make it a regular part of training.

If you want or need to ruck faster, try a ruck shuffle: It’s faster than a walk but slower than a run, a foot always maintaining ground contact. A speed walk.

Does walking with my kid in a backpack kid carrier count as rucking?

Short and long answer: Yes. Plus, you get bonus points because the load moves around, cries at you to ruck faster, and can even spontaneously projectile vomit on you.

Anything else I should know?

Short and long answer: If you're interested in learning more about the science of rucking what makes humans strong, healthy, and happy, check out The Comfort Crisis.

And make sure you’re subscribed to this newsletter, which covers all sorts of information that’ll help you ruck and live better.

Still have questions? Become a Member and drop them in the comments.

Have fun, don’t die, walk with weight.

-Michael

Sponsored by Momentous

Momentous made me feel good about supplements again. Over 150 professional and collegiate sports teams and the US Military trust their products, thanks to the company’s rigorous science and testing. I don’t have the time or desire to cook perfectly balanced meals that give me all the necessary nutrients and protein I need (let’s face it, few of us do!). So I use their Recovery protein during hard workouts; essential multivitamin to cover my bases; creatine because it’s associated with all sorts of great things; and Fuel on my longest endurance workouts on 100+ degree days here in the desert (because Rule 2: Don’t die). And I also love (love!) that Momentous is researching and developing women-specific performance supplements.

**Use discount code EASTER for 15% off.**

Sponsored by Inside Tracker

Your blood holds stories—lots of them. It can reveal critical information about your risk of heart disease, your metabolic health, recovery, endurance, inflammation, and much more. And yet, to get the most important information, you need to go deeper than the lab work your doctor has you do each year.

Enter Inside Tracker, created by researchers at Harvard, Tufts, and MIT. They make it easy to get deep blood work, providing analysis that can tell you about risks in your future and help you make guided decisions that will help you live and perform better, longer. Results from my own tests led me to alter a few health habits, and I’m better for it.

**Use discount code EASTER.**

Sponsored by GORUCK

When I decided to accept sponsorships for this newsletter, GORUCK was a natural fit. Not only is the company's story included in The Comfort Crisis, but I've been using GORUCK's gear since the brand was founded. Seriously. They've been around ~12 years and I still regularly use a pack of theirs that is 11 years old. Their gear is made in the USA by former Special Forces soldiers. They make my favorite rucking setup: A Rucker 4.0 and Ruck Plate.

**Use discount code EASTER for 10% off**

Michael- great article. I started rucking in 2021 and haven't looked back. Can you create a 'supermedium' workout plan? Something sustainable for the average person that includes cardio, strength training & mobility? Maybe something you and Dr. Doug can put together? Just a thought. It would certainly be something I'd pay for!

Yes please to more on women and muscles!

Also, I tend to get the pain in the back of the neck rather than the shoulders, similar to when doing a lot of sit ups and you feel the neck strain. Is that normal and will it improve as a persevere?