How To Love Your Job

The science of job satisfaction and how any job can be fulfilling with the right mindset tactics.

Post summary

We’re exploring the counterintuitive relationship between work and happiness. Many of these ideas were shaped by my time living in a Benedictine monastery.

Roughly half of all people are unsatisfied with their jobs.

But being the other half—the “extremely satisfied” workers—is mostly determined by your mindset about your job.

Any job can be fulfilling and rewarding if you learn the right mindset tactics.

We’ll explore three ways you can improve your mindset around work, including:

What scholars get wrong about modern jobs and happiness.

A framework for viewing your career that’ll leave you happier and healthier.

The surprising science of retirement and mental health and what we can learn from it.

Housekeeping

ICYMI, Two Percent is back on Substack. This is why.

Full access to this post—and all Wednesday and Friday posts—is for Members of Two Percent.

🚨 But here’s some good news: There are a handful of hours left to claim return-to-Substack annual Membership discount. Save 15 percent on a yearly Membership now.

Podcast version of this post

🔊 Reminder to Members: Here’s how you set up your Member podcast feed on your podcast player of choice.

The post

As I mentioned in Monday’s post, I was naive when I started Two Percent.

First, I thought this project was me writing to you. But I quickly realized we have a community here—it’s actually us writing, thinking, and creating together.

Second—and I didn’t mention this on Monday—I initially saw Two Percent as a side project.

I didn’t know that this newsletter would become one of the two pillars of my career.

Last December, I even left my job as a full-time professor at a university so I could dedicate my time to writing Two Percent and more books.

Moving back to Substack has reaffirmed my career in writing.

Today’s post is about work and how to make it better. Work takes up about 90,000 hours of our lives. And our relationship to those 90,000 hours determines our day-to-day experience of life, our mental health, happiness, and all the other markers of being human.

Yes, we all have moments where we complain about our careers.

For example, I have days when the words flow like sewer sludge. Or afternoons packed with noise from my publisher.

And many of us long for the day we can retire and stop working altogether.

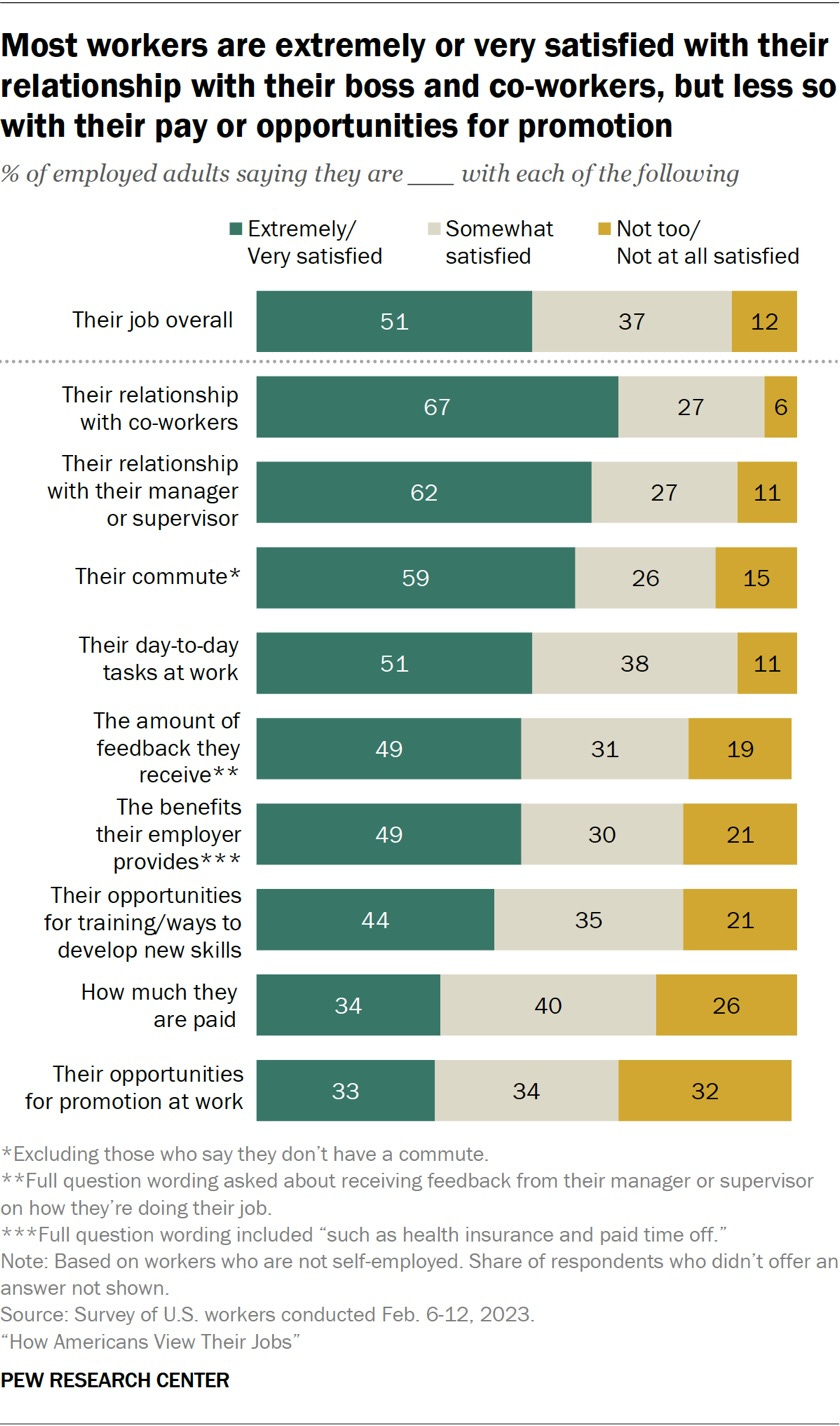

The Pew Research Center recently conducted a poll of more than 5,000 workers.

The big stat: It found that 49 percent of us are either just “somewhat satisfied” or “not satisfied at all” with our jobs. The good news: Fifty-one percent of us are “extremely satisfied” with our jobs.

More details and findings from the poll:

But despite its occasional pains—which vary depending on the job—work is actually one of the best things for your health and wellbeing. And being one of the 51 percent of “extremely satisfied” workers is mostly determined by your mindset.

This is a topic I first started to grasp while riding shotgun in a single-cab, 1980s-era Chevy Pickup that was rocketing down a dirt road in New Mexico’s Gila National Forest.

At the wheel was a 20-something Benedictine monk. He had the tonsure haircut, the full-body robes, the giant cross dangling from his neck—this guy was all monk all the time.

The pickup’s bed was filled with all sorts of tools: a generator, electrical wire, wire cutters and strippers, shovels, pick axes, and more.

Our job was to re-arrange the New Mexican landscape and run electrical wiring to a new convent, where the nuns live.

Usually, I feel the same about landscaping as I do about taxes and traffic jams. But there was something to this labor that felt satisfying and worthwhile. And why was that?

Some context behind my manual labor with the monk: In the fall of 2022, I spent a week living and laboring with a group of Benedictine monks in a monastery. These men had dedicated themselves to a life of “ora et labora”—pray and work—for something larger than themselves.

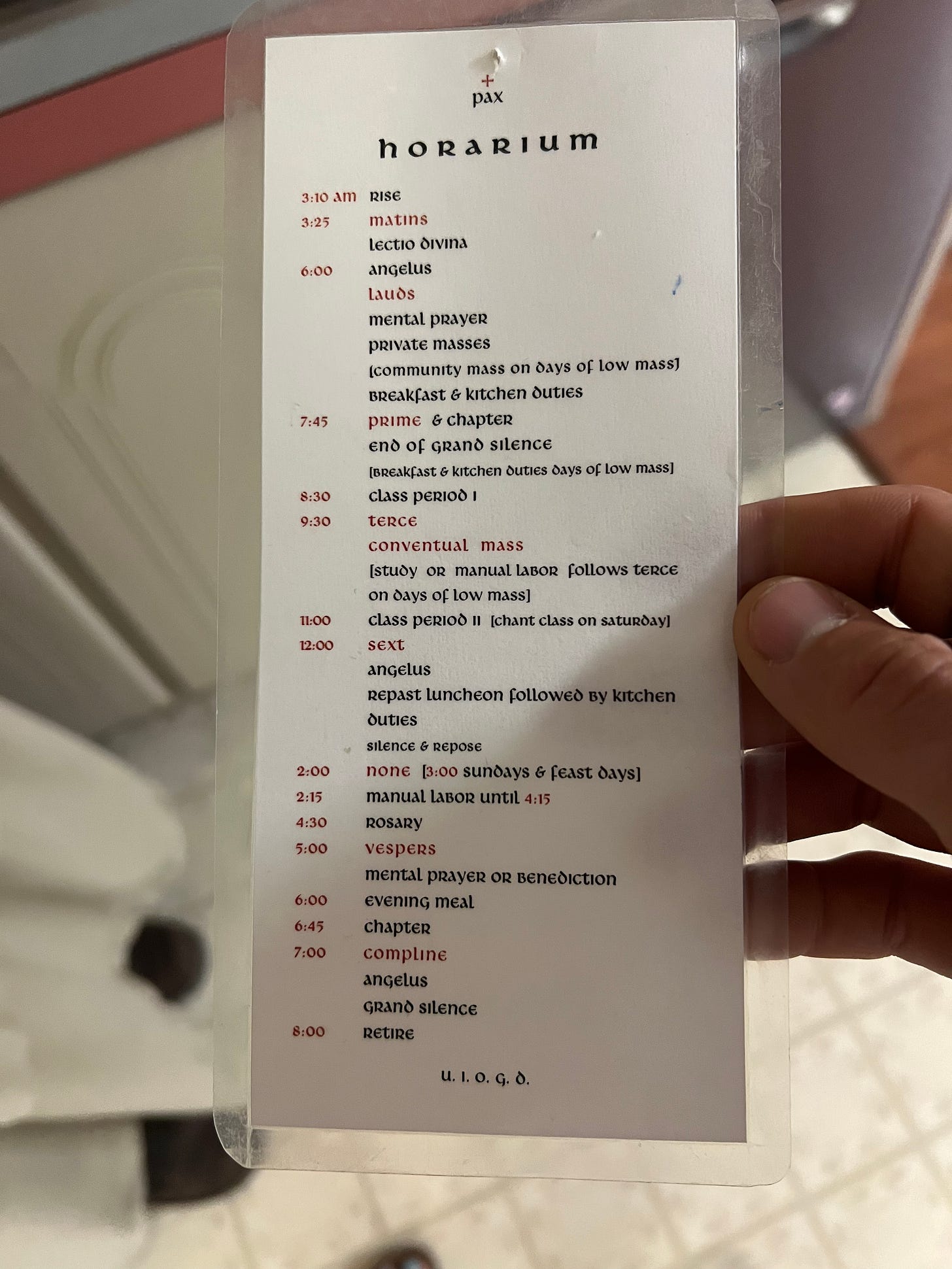

To my eye, the life of a monk looks a lot like faith-based bootcamp. A monk or nun’s day begins with prayer in the chapel at 3:25 a.m. From there, they’ll run through six other prayer sessions in the chapel, two to four hours of hard manual labor, intense studying, and more.

Talking is frowned upon throughout most of this. Monks and nuns are both celibate and out of regular contact with the outside world.

Here’s a daily schedule the brothers gave me when I arrived:

And yet research shows that Benedictine monks consistently score higher levels of happiness and life satisfaction than the average American. (And we everyday Americans can sleep in, eat what we want when we want, watch YouTube on a smartphone, get married, and fully engage in pretty much every other modern wonder).

One of the head monks put it to me this way: “In spite of the austerity, in spite of the workload, in spite of all these things that might seem like a hardship and total waste of time, these people are all happy.”

Much of their happiness comes down to how they view work.

As I go through my own work transitions and have conversations about work with my mom—74 years old and still working—what I learned from the monks has been exceedingly helpful.

Here are three takeaways.

1. Your job isn’t bullshit

Section summary: Some academics argue many modern jobs are “bullshit.” But further investigation reveals it is actually their argument that is bullshit.

My experience at the monastery came up in one popular podcast I appeared on.

The host pointed out that if the world’s monks and monasteries went away, the world would continue working just fine. But that wouldn’t be the case if, say, all the nurses went away.

The implication was that the work of the monks was somewhat, well, useless.

Some academics have argued that many modern jobs are futile. For example, in 2013, the famed and late anthropologist David Graeber proposed a theory he called “Bullshit Jobs.”

He described it in a 2018 bestselling book of the same title. Graeber claimed that anywhere from 30 to 60 percent of all jobs today are “bullshit,” and that the ratio of bullshit jobs is increasing over time.

He defined bullshit jobs as:

“A form of paid employment that is so completely pointless, unnecessary, or pernicious that even the employee cannot justify its existence even though, as part of the conditions of employment, the employee feels obliged to pretend that this is not the case.”

He gave examples of assistants, lawyers, lobbyists, compliance officers, quality control specialists, middle managers, greeters, and many more.

Working in one of these “bullshit jobs,” Graeber claimed, makes us unhappy. He wrote that it creates “profound psychological violence.”

But Graeber’s idea was just that: a theory from a tenured academic who had summers off and looked at everyone else working summers with less job security than him and assumed we must hate it. It was a notion based on anecdotes.

When a team of scientists from the University of Cambridge analyzed all the data, they found that it was actually Graeber’s theory that was bullshit.

After rigorous analysis, the Cambridge scientists found the following:

Yes, if you believe your job is useless, you will likely experience poor wellbeing.

But, they wrote, “our findings contradict the main propositions of Graeber’s theory. The proportion of employees describing their jobs as useless is low and declining and bears little relationship to Graeber’s predictions.”

In fact, many of the jobs Graeber identified as being “bullshit jobs,” reported the highest levels of job satisfaction.

The takeaway is that no job is useless so long as you’re treated well and realize that it’s probably helping someone somewhere. We all contribute. Understanding this is a key to being one of the 51 percent of people who are extremely satisfied with work.

Consider the monks. It’s useful to view their work—and really any job—through the lens of what they contribute to their community. If any one of the monks stopped working, their community as a whole would crumble. For example, if the monk who farms and feeds the chickens quits, the rest of the monks won’t eat.

The takeaway

Feeling like your job is helpful depends on how you frame it. Satisfaction is a mindset.

Consider Mary Ruth Robinson. She’s an 86-year-old greeter at a Walmart in Kentucky.

You could argue that greeters at Walmart are unnecessary. But Mary Ruth treats her role as an opportunity to improve the lives of others. And she does.

Be like Mary Ruth. Find the parts of your job that are helping someone somewhere. They undoubtedly exist.

And they’re worth remembering and leaning into over and over.