An astonishing story of perseverance and stoicism shows us how to think about modern life.

You’ll learn: The science of first-world problems, and how it can be the ultimate mental health and happiness hack.

Housekeeping:

We just launched a killer referral program. In short: You get free stuff for referring others to 2%. Use the button below.

The 2% shop is also up and running. 2% hats, ruck patches, and more are going quick.

Thanks to our sponsors GORUCK, Maui Nui Venison, and Momemtous Nutrition. I get many sponsor inquiries and limit sponsorship to products I use daily. They’re all gracious enough to offer 2% readers discounts on any of their products. Use code EASTER.

Thanks, everyone, for reading and listening (audio is at the bottom for Members). Become a Member if you want to read and listen to the best 2% content.

Now onto today’s post …

I’d planned to write a post about new, fascinating research on taking the stairs. It’s a study that hammers home why we should all be 2-Percenters. But we’ll get to that next week.

If you listened to the audio of Monday’s post, you know that Monday, July 24th, was Pioneer Day in Utah.

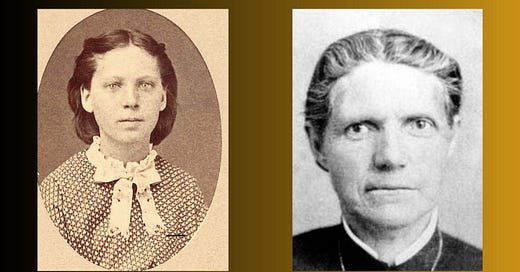

I grew up in that state. The holiday always reminds me of a family member who lived in the 1800s. Her life story is the epitome of resilience and perseverance. It can give us some life-enhancing perspective on modern life and insight into a critical psychological concept called prevalence-induced concept change.

Pioneer Day celebrates the arrival of Mormon settlers in Utah. Mormons in the 1830s and 1840s were persecuted for their faith. They’d been violently driven out of Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois. Their leader, Joseph Smith, was assassinated by a mob in Illinois.

Smith’s successor, Brigham Young, realized that Mormons would probably always be persecuted so long as they lived in the United States. So he decided they should all escape the U.S. and establish a Mormon colony somewhere in the wild area that was then Mexico.

In 1846, Young gathered about 1,600 from the faith. They loaded handcarts and headed west into a savage landscape with no particular destination.

After months of trekking, historians explain what happened next—the basis for Pioneer Day—on July 24th, 1847:

Young and his followers emerged out onto a broad valley where a giant lake shimmered in the distance. With his first glimpse of this Valley of the Great Salt Lake, Young reportedly said, “This is the place.” That year, some 1,600 people arrived to begin building a new civilization in the valley. The next year, 2,500 more made the passage. By the time Young died in 1877, more than 100,000 people were living in the surrounding Great Basin, the majority of them (Mormons).

My great, great, great, great, (great x ?) aunt, Nellie Unthank, was one of those 100,000 pioneers. But arriving in Utah wasn’t exactly a first-class flight.

Two Frozen Legs, One Butcher’s Knife

Nellie was nine when her family and a group of 500 other Mormons left Iowa City for Utah, pulling handcarts loaded with their belongings. This was in May of 1856.

Things went well for most of the journey. But when the team reached Wyoming in October, a freak early-season blizzard hit. It slowed them to a crawl. Snow piled, temperatures plummeted, and they began running out of rations.

Every moment became life-or-death. Nellie’s father, for example, slipped into a cold river the group was attempting to cross and died from hypothermia. Her mom died from exposure five days later.

Word of the team’s situation eventually reached Salt Lake City. Leaders sent a team of rescue wagons, who found the group buried in snow near the Platte River Bridge in Wyoming. One-hundred fifty had died.

When Nellie finally made it to Utah in late November, her feet were frozen.

Doctors knew she’d die without a medical intervention. One old news report described what happened next:

Nellie was strapped to a board to hold her down while the crudest of tools, a butcher knife and a carpenter’s saw, was used to amputate her lower legs, not far below the knees. As if that were not bad enough, the surgical procedure was (without pain medication and) so primitive that the wounds healed badly and bone continued to protrude from the end of her stumps.

Because the crude surgery left her bones exposed, Nellie couldn’t wear the wooden prosthetics of the time. So she wrapped her exposed bone in leather and got around by crawling on her knees.

She crawled the world in constant pain the rest of her life.

Historical records show that she went on to have six children and was about as productive as everyone else in the community. She never complained and made a solid income weaving clothing and other goods.

Nellie lived to 69. A local leader wrote about her after she died:

In memory I recall her wrinkled forehead, her soft dark eyes that told of toil and pain and suffering, and the deep grooves that encircled the corners of her strong mouth. But in that face there was no trace of bitterness or railings at her fate. There was patience and serenity, for in spite of her handicap she had earned her keep and justified her existence. She had given more to family, friends and to the world than she had received.

On Prevalence-Induced Concept Change

A couple weeks ago, I was on a flight to Salt Lake City from San Francisco. It was one of those flights that was not only late, but also came with turbulence, screaming babies, downed wifi, and one person with a nut allergy that ruined everyone else’s ability to eat peanuts.

I found myself, let’s say, irritated.

In chapter four of The Comfort Crisis, I wrote about an idea called “Prevalence-Induced Concept Change.” Harvard psychologists discovered it in a series of studies in 2018. You can think of it as “problem creep.”

It explains that as we experience fewer problems, we don’t become more satisfied. We just lower our threshold for what we consider a problem.

We end up with the same number of troubles. Except our new problems are progressively more hollow. It’s why we can often find an issue in nearly any situation, no matter how good we can have it relative to the grand sweep of humanity.

We are always moving the goalpost. There is, quite literally, a scientific basis for first-world problems.